By Mark Quirk

How do we stay healthy, avoid chronic disorders, and reduce the risk of infections often associated with older age?

Is it all in our genes? According to a 2016 review paper by Prof. Stephen M. Rappaport, using published data on identical twins, on average, only 18.5% of chronic disease risk in later life could be attributed to genes [1]. If people with exactly the same genes rarely share the same chronic diseases, it’s fair to say that genes are not the primary driver.

How we’ve lived our lives becomes more impactful on our health the longer we live. We often use the phrase lifestyle to describe how we live, though I realise not everyone likes it; most of us at least know what it means… or do we?

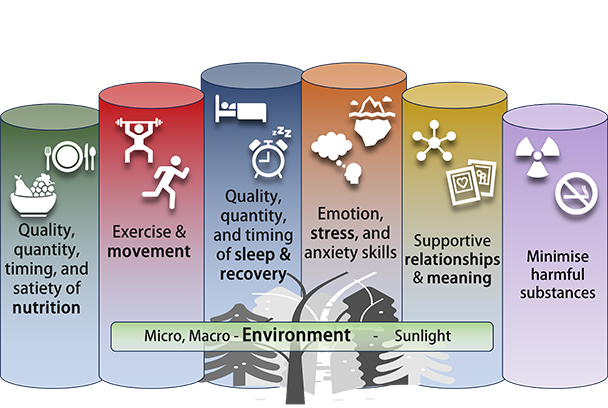

Over the years, I’ve asked many people what they think is included in ‘lifestyle’, and it’s pretty normal for my definition to be different. So, I started being more specific about what I meant – it’s not that anyone’s definition is right or wrong, but it’s helpful to talk about the same things. Primary Prevention’s Pillars of Healthspan came from those conversations, plus the environment in which each exists.

Quality, quantity, and timing of nutrition

Nutrition science is tough. We want big groups of people to consume a specific diet where we could be sure that:

- They all ate the same food.

- At the same time.

- After doing the same things.

- At the same age.

- With the same levels of stress.

- Doing nothing different from each other.

- For years and years.

This would be ideal… or should I say idealistic. We can’t do this experiment, everyday human lives are messy. So, nutrition scientists try to control for a wide range of variables whilst bringing together targeted short-term studies with a small number of people (e.g. randomised controlled trials) with longer-term studies that are less specific but with many participants (epidemiology) to try and understand the impact of particular foods, timing, and eating patterns.

Creating an individualised evidence based diet advice can, therefore, be difficult. So we start by looking for multiple sources of evidence, epidemiology studies supported by targeted studies, to make informed choices for conducting personal experiments – testing how this food or food pattern affects me!

Exercise and movement

I don’t think I need to convince anyone that we need to move our body to help it work efficiently, do I? Ok, just one example.

The lymphatic system is a bit like the fluid waste system of the body. Blood delivers fluid and nutrients into our cells and organs, and the lymphatic system removes what the cells have finished with. But, unlike the cardiovascular system, which has a dedicated pump to keep things moving, the lymph primarily uses the skeletal muscle contractions to help it on its way, transporting all that waste through the cleaning filters of the lymph nodes before transporting it back into the bloodstream.

The lymphatic system doesn’t require us to go to the gym or run a marathon, but it is an excellent reason to get up from our desk or settee every thirty or forty minutes.

However, exercise does add a whole new dimension to the efficient running of this extraordinarily complex thing we call our body. And when you consider that by default we’ll lose up to 39% of our muscle mass between the ages of 20-80 years [2], it’s no wonder that opening a jar becomes difficult as we get older (not to mention getting out of a chair).

Then, there’s the correlation between cardiorespiratory fitness and all-cause mortality (dying for any reason). Firstly, there is one. You might not be surprised to hear that those who are very fit tend to live longer (and almost certainly better) than those who are very unfit by a considerable margin [3].

So, move, sometimes quickly and sometimes with heavy things.

Quality, quantity, and timing of sleep

People quote the Bon Jovi song – “I’ll sleep when I’m dead.” It’s an interesting idea, all the wasted time sleeping when we could be enjoying ourselves or finishing an important project. But it’s a terrible idea if you want to perform optimally and live well.

Sleep is a critical part of our body’s overall repair and recovery strategy, which is heavily influenced by an internal timing system synchronised with our 24-hour day and night cycle. It’s called the circadian rhythm and runs at its best when the timings are consistent.

While sleeping, our body removes the dead wood and builds new infrastructure so our body and mind can operate more efficiently. When we don’t give it this opportunity, we will eventually reap the cost of sleep disruption.

But what if we struggle to sleep? It’s a widespread problem, and we look to sleep science for understanding while focusing on your situation – and hopefully, restore some normality because it is worth the investment for a quality nights sleep.

Emotion, stress, and anxiety skills

Have you ever:

- Said something you wish you hadn’t said?

- Done something you wish you hadn’t done?

- Thought something you wish you hadn’t thought?

- Felt in a way you didn’t want to feel?

If so, welcome to the human race.

Emotion is a powerful driver of thoughts and behaviour, and sometimes leads to pleasure and delight, but can also lead to the all the too common experiences of stress and anxiety. I often say that resilience is not the absence of stress or discomfort; there is no need for resilience if something doesn’t feel difficult. And we learn resilience.

How we engage in the physical and mental processes of daily life is based on skills we have learned, from our earliest days in the playground right through to the experiences we have today. And given how impactful emotion can be, it’s worth proactive practice to build the skills of emotional resilience.

Supportive relationships and meaning

We’re social creatures. Even those of us who would describe ourselves as more introverted, enjoying our own company, are still fundamentally social. This isn’t about our preference for social engagement, whether we enjoy parties or a bath with a good book; it’s about biological processes that lead us to connect with others – whether from afar, with one other, or a hundred others.

One of the longest-running social science studies intended to examine what leads to success in life. It started tracking 268 Harvard University 2nd-year men in 1938, concluding in 2009 [4], making way for a second-generation study (which, of course, also includes women!) [5].

For the last 40 years, George Vaillant has been the director of the project. In an interview in 2009, from his experience and the enormous amount of data they had gathered over 71 years, he was asked to summarise what they had learned made a good life [6]. His summary:

“The only thing that really matters in life

George Vaillant

are your relationships to other people.”

Success, from this study, is not about material possessions or career highs but about the quality of our connections with others – yes, not the quantity of connections, but the quality of the relationships.

Meaning in life doesn’t have to be about changing the world; it can be simple and is always personal. As social creatures, it seems that what we find meaningful most often relates to other people.

Supportive relationships and meaning relate to healthspan. The Harvard study supports this, and going back to the blue zones, repeatedly, we see those who live well longer have robust relationships and meaningful lives.

Minimise harmful substances

The most obvious candidates in this category are tobacco products and alcohol, though I’ll often include ultra-processed foods here too. Minimising harmful substances is a pretty straightforward general argument regarding health. The issue is more likely with alcohol, and a myriad of confusing evidence about its value. However, the UK chief medical officers lowered the recommended weekly safe units to twelve for men and women a few years back.

Environment – micro and macro

Environment is number seven– not one of the pillars, but the foundation of all the pillars. Everything is affected by its environment.

From a macro or big picture, air pollution, the quality of our food and resources, noise pollution, access to clean water, etc. To the micro or targeted to each of the pillars, for example, to sleep well, it’s helpful to feel safe and have a dark, cool, quiet room.

Personalised

There’s good evidence to support each of the pillars, but which is most worthy of your focus and how to apply it to your daily life is rarely so straightforward and often requires experimentation. If the advice to exercise, eat well, and get enough sleep were enough, fewer of us would have preventable chronic diseases.

So we loop around a process:

- Assess where you are now, including your current health status and how you live.

- Prioritise action steps from where you are now toward the goals of where you want to be.

- Invest your time and effort to meet those goals.

- And repeat.

Together, the intent is to improve your health and wellbeing for today and extend your healthspan for tomorrow.

References

1. Rappaport SM. 2016 Genetic factors are not the major causes of chronic diseases. PLoS One 11, 1–9. (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0154387)

2. Lexell J, Taylor CC, Sjöström M. 1988 What is the cause of the ageing atrophy? J. Neurol. Sci. 84, 275–294. (doi:10.1016/0022-510x(88)90132-3)

3. Mandsager K, Harb S, Cremer P, Phelan D, Nissen SE, Jaber W. 2018 Association of Cardiorespiratory Fitness With Long-term Mortality Among Adults Undergoing Exercise Treadmill Testing. JAMA Netw. open 1, e183605. (doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3605)

4. Shenk JW, Vaillant G. 2009 What Makes Us Happy? Atl. See http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/06/what-makes-us-happy/307439/2/?single_page=true.

5. In press. Harvard study of Adult Development. Harvard Med. Sch. See https://www.adultdevelopmentstudy.org/.

6. Vaillant GE. 2009 Yes, I Stand by My Words, “Happiness Equals Love—Full Stop”. Posit. Psychol. News See http://positivepsychologynews.com/news/george-vaillant/200907163163.